Did You Say Hip Hop?

Fatou Kandé Senghor

17h30

For a long time in Senegal, knowledge, creativity and the spoken word were the privilege of the French-educated closely supervised elite, then that of the Negritude movement led by Aimé Césaire and Léopold Sédar Senghor. In the 1980s, the eld of expression remained limited to the elite, to the politicians and religious families that led millions of fervent Senegalese followers. The eld of protest was still at this point the reserve of students, opposition parties, trade unionists and writers. Even so-called “local” music failed to convey the feelings of young people, who nonetheless existed and who were beset by several major dif culties. Despite unbridled urban growth and the lack of resources to cater for the massive rural exodus towards the economic capital, not the slightest subversive movement or controversial tune appeared.

In a country where the youth accounts for almost two thirds of the population, it goes without saying that access to the spoken word had to be achieved, by fair means or foul. Sur ng the global wave of the hip hop movement, Senegalese youth succeeded in digging deep into the roots of their modernity, urbanity and creativity to nd a place where speech was freer. Quite simply a place free from censor- ship, whether the artistic content be exhaustive or not. Later the youth reclaimed “local” languages, which neither literature nor scienti c disciplines had managed to use for the people. In doing this, the youth saw a way to rid themselves of complexes and of the tyranny of academia, the elite and the politicians who ignored this orality even though it had been a cornerstone of their identity. This was the orality of their people, their communities, their clans, their customs and traditions, which they didn’t have the luxury of swapping for the gimmicks of “Western civilization”. Hip hop was a perfect tool of transition to create and grow in a more demo- cratic world. Then, in light of new alliances with

the rest of the planet, it was no longer adequate to simply dream from the country’s riverbanks; other alternatives for construction were conceivable. The world of adults was all ears now and granted them the right to take part in debates on societal affairs.

About Fatou Kandé

Fatou Kandé Senghor is an artist and lmmaker who produces documentaries, television shows and ction. She also trains young students and youth with learning dif culties in video-making. Her docu- mentary lm entitled Giving Birth, which portrays the enigmatic Casamance-based sculptor Seyni Awa Camara, was presented at the Venice Biennale in 2015. She has published several essays discussing gender, urban cultures and African cinema.

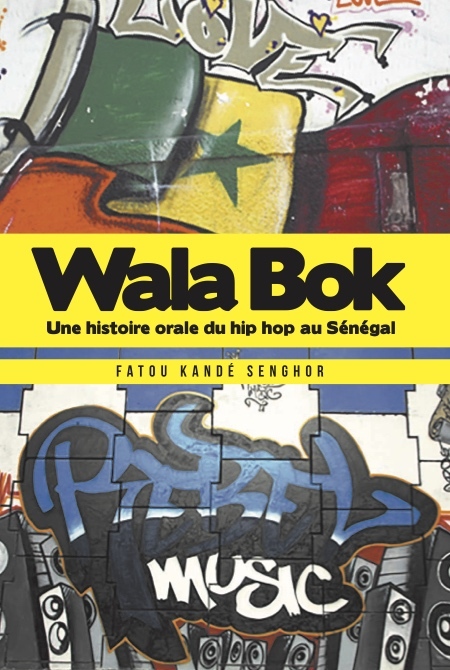

Kandé Senghor is the founder of Waru Studio, an arts center that brings together young artists, lmmakers and researchers to explore the nexus between art, technology and politics in Africa. In 2015, she published WALABOK, An Oral History of Hip Hop in Senegal (Amalion Publishing). The publication is an anthology of two generations of artists that make up the hip hop movement in Senegal. It serves as a basis for a television series that deals with Senegales youth through the lens of hip hop; tackling both the ills and positive aspects of our society.

Kandé Senghor’s artistic practice combines photography, lm, public instal- lations, writing and research in which she explores intimate concepts such as identity, community, religion, history and geography. Her primary passion is documenting social transformation in order to better reveal how perceived sacred texts, poetry and the legends of oral tradition inform modern life. Kandé Senghor likes to blur the dichotomy between ancestral heritage and religious practice (Islam, Judaism and Christianity) in order to challenge and complicate expectations and stereotypes. She lives and works in Thiès.